↑ San Diego’s Trolley, the first U.S. light rail system, kicked off the 1980s craze for this hybrid mode.

Sam Hodgson/Bloomberg via Getty Images

This article recaps on the content and the history of the reintroduction of linght rail into certain US cities

by LAURA BLISS – 17 Jan. 2020

by LAURA BLISS – 17 Jan. 2020

Out of Darkness, Light Rail!

In an era of austere federal funding for urban public transportation, light rail seemed to make sense. Did the little trains of the 1980s pull their own weight?

When San Diego opened its light rail system in 1981, Mayor Pete Wilson declared it “a good idea whose time has come again.’” The bright red train cars, known as “the Trolley,” harked back to the urban railway that spanned 165 miles across metropolitan San Diego until 1949. As in so many North American cities, that streetcar system was ripped out as the automobile era dawned.

But the San Diego Trolley was built with a different spirit and purpose than its predecessor. It was light rail. And from San Diego, the new mode would spread across North America. Far cheaper to build than a subway, faster than a streetcar, and perhaps more alluring than a bus, light rail was seen as the answer to congested highways, growing populations, and civic fantasies of a dozen U.S. cities in the 1980s and early ‘90s.

Yet local leaders in mid-sized cities still wanted—and needed—public transit. Highways were becoming more congested as urban growth patterns sprawled to the suburbs and downtown centers emptied out. In the 1970s, Edmonton, Alberta had been the first in North America to adopt light rail technology, which had started in Germany as a hybrid of tram-grade cars and rapid-transit-grade tracks. (Be warned: The term “light rail” is distinct from “streetcar,” although the difference between the two modes is murky; the latter usually—but not always—refers to historical urban railways that run in mixed traffic, with shorter routes, slower speeds, and more frequent stops.) Light rail seemed to have many advantages: It could run in existing rights-of-way, didn’t require digging tunnels or building aerial supports, and the technology was much less complex than heavy rail. “It’s more like an amusement park ride,’” an executive at the American Public Transit Association reportedly quipped at the ribbon-cutting of the Trolley.

Certain people, in particular. Planners believed that light rail could draw a new market of riders. Car-owning commuters who lived in suburbs but might be interested in alternative transportation options were seen as the natural light rail constituency. Buses carried a stigma—a racist, classist stigma—but trains had cachet. “The idea was that if you provided a reliable, high-quality rail service, that might appeal to those individuals,” Brown said. That’s why virtually all light rail systems followed a “hub and spoke” layout, with long arms reaching out to the suburbs rather than focusing on the city core.

Compared to “captive” riders who relied on transit as their primary mode, these “choice” riders—terms have since fallen out of fashion in transit lingo—were generally better off and able to pay higher fares. Multiple studies have since proven that light rail systems do indeed recoup more revenue from passenger fares than buses do—in fact, the San Diego Trolley still boasts one of the highest “farebox recovery ratios” in the U.S.

All of this was important to 1980s planners. President Ronald Reagan cut federal support for transit by 32 percent in his first year in office, and later tried to slash operating subsidies and capital investment by another two-thirds. His characterization of Miami’s heavy rail metro in March 1985, which was just 10 months old and falling short of ridership projections, is a good snapshot of his views. “In Miami,” Reagan told a conference of county officials, “the $1 billion subsidy helped build a system that serves less than 10,000 daily riders. That comes to $100,000 per passenger. It would have been a lot cheaper to buy everyone a limousine.”

As the federal government withdrew support for transit projects (and for just about every type of public benefit, especially within cities), light rail was a comparatively modest ask by local governments, one they could pay more for themselves.

Meanwhile, while cities have continued to invest in light rail, it has often come at the expense of bus service, thus disadvantaging poorer riders of color.

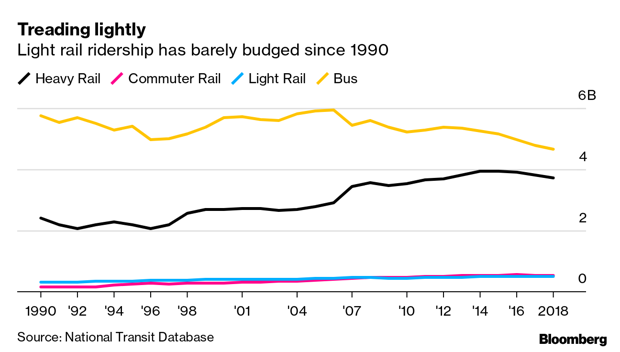

“It’s not like [light rail systems] are unused,” said Jonathan English, a doctoral student at Columbia University (and CityLab contributor) who specializes in the history of urban transit in North America. “But after dozens or even a hundred kilometers of light rail, the effect of these transit systems as transportation has been pretty marginal.”

Part of the problem was the alignment of many light rail systems. Constrained by strict federal funding requirements, planners often laid their tracks along freeway medians and busy arteries to save money; that means riders often had to trek across multiple lanes of speeding traffic to board, and stations often had to be sited far from walkable residential areas. There was also little integration with existing bus networks, or vice-versa. “It’s good if you can walk to the light rail station, but even in cities with extensive networks like Portland, only a tiny percentage of the region’s population can do that,” English said. Fast, frequent bus networks could feed more riders to these stations, but few cities have focused investment in buses until very recently. English likens such unsupported light rail systems to “skeletons without a body.”

All told, the legacy of the era’s light rail fever is mixed. But from a transportation perspective, it was a more practical trend than the more recent mania for downtown streetcars. The dinky little lines built in gentrifying sections of Detroit, Cincinnati, Washington, D.C., and other cities in the last decade make basically zero pretense of serving transit riders; these short loops of notoriously slow conveyances are instead built to drive up property taxes. Nothing wrong with that on its face. But as greenhouse gases from vehicles rise, and as the federal government continues to starve transit funding, streetcars are an uncomfortably old-fashioned look—and use of local tax dollars.

By comparison, light rail systems—the flawed children of Reagan-era compromise—seem a lot more rational. They might not have been able to lure Americans out of their cars, but their time may yet come.

View original article at www.citylab.com

Commentaires récents